Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about how much strength is “enough” for athletes and how much time should we spend developing it.

Obviously, different sports/positions have different requirements, but the basic question is always the same – how much time and effort should be put into developing huge amounts of strength compared to working on other physical abilities such as speed, endurance, flexibility, agility, footwork, or sport-specific skill work. I’ve talked to several coaches about this, and I haven’t really found a perfect answer.

Probably the most intriguing thought was to spend as little time as possible while still getting results. That really struck something in my mind and took me back to listening to Mike Gittleson talk while I was in graduate school at Michigan. He talked a lot about the dose:response relationship, and how applying the minimum dosage is always prudent as long as the results are there.

That makes a lot of sense, especially when you consider all of the other stuff that athletes need to work on. Unless we’re talking about powerlifting or weightlifting, strength is almost never the most important attribute of a successful athlete.

Yes, there is a baseline level of strength that seems to be needed, but enormous amounts of strength are usually not requisites for athletic success. (Keep in mind that I don’t train competitive weightlifters or powerlifters.

Related: Why Stronger Athletes Make Better Athletes

If you do, then you probably have a very different perspective.)Yet, we as strength coaches often get caught up in the “numbers” game.

We want to have our athletes bench, squat and clean (or any other lift) a lot of weight. But, if a football, basketball, or baseball player can already squat 400 lbs, is it really necessary to shoot for 420? Is it worth the time and energy that is required to continue progressing?

Is it worth the risk? Of course, most people aren’t at that point, but trying to lift really heavy weights may not be completely necessary for everyone. I’m not saying we shouldn’t try to get stronger. I’m not in that camp at all. I think every athlete should be on a strength program of some sort.

I just wonder if we over-emphasize max strength and spend (relatively) too little time on other things compared to the time we spend on strength.

Then I started thinking about what the most important qualities in athletes are. Of course, sport skills are always going to be king. After that, there’s quite a bit of variety depending on the sport, but there aren’t too many sports where speed, agility or “explosiveness” aren’t important.

Being in excellent shape is also usually a key component to many sports. Mobility and injury prevention are also areas that we should probably spend some time on. Core strength has gotten a lot of attention lately, and athletes should probably work on that to some degree. Muscle “stiffness” has also been talked about a lot and should certainly be addressed in a S & C program. The point is that there are a lot of different factors that go into athleticism.

Strength is related to many of these qualities, but I feel like we often put more of an emphasis on this quality than all of the others. Sure, there’s good reason to strength train, but why are we so enthralled with big numbers?

Why not spend a little less time on strength and a little more on the other factors listed above? Why do many coaches list their powerlifting numbers on their resumes? Are the numbers really THAT important?

Any coach who brushes over that other stuff and has an athlete spend all of their time on strength work is missing the target. I believe coaches who do this are probably doing it because they don’t know how to do anything else, which is pretty sad.

I agree that most young athletes could really benefit from additional strength. Most high school athletes are not overly strong, so there’s certainly plenty of room for improvement. In most cases, they haven’t hit that “strong enough” point…..whatever that point may be.

Related: Use The Dynamic Effort Method to Build Explosive Athletes

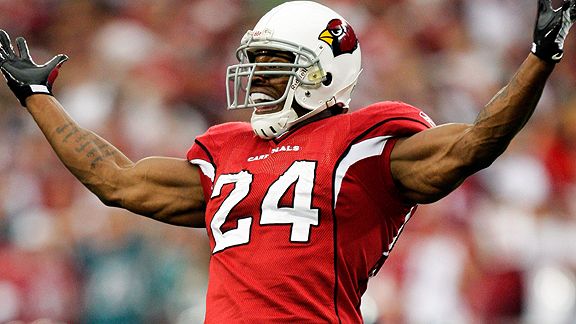

In college, a lot of athletes with a decent strength coach probably hit that point somewhere along the way, and most professional athletes have probably hit it. Not always, but usually. They’ve obviously enjoyed a lot of success in their sport, so you’d assume that they are “strong enough” for that endeavor or they wouldn’t have gotten to where they are.

So, the conversation that really got me thinking was when I was talking to WVU S & C Coach Darl Bauer (no I didn’t misspell his name…it’s spelled that way) about all of this.

At the time, San Diego Chargers TE Antonio Gates was working out with me,  and he told me that he hadn’t hit the weights that hard in years. He said that he lifts, but not that hard and that he’s not that worried about strength.

and he told me that he hadn’t hit the weights that hard in years. He said that he lifts, but not that hard and that he’s not that worried about strength.

He wanted to focus on other things he felt were more important. Now, Antonio is a very gifted athlete with plenty of speed, strength and size, so it’s not like I’m talking about some genetic trash can here. He’s a stud. But, it hit me that if a Hall of Fame football player wasn’t that worried about his strength, then was it really that important?

So, I asked Darl about his TE at WVU at the time. He said the guy was a freak – amazing strength, speed, everything. Really, really strong and puts up huge numbers in the weight room. I asked him if he was starting his own team, would he take this kid or Antonio Gates?

He laughed and said Gates (no offense to the kid at WVU, but we’re talking about Antonio Gates here). When I told him about Antonio’s lifting habits, he kind of paused. Then, he responded with the age-old argument “Just think how much better he might be if he lifted harder.”

I told him that might be true, but then I asked how much better than Hall of Fame can you get?

We both laughed and went back and forth on the topic for a while, but this whole thing really put things into perspective for me.

I also looked into Usain Bolt a bit while I was thinking about this. From what I can tell, Bolt lifts weights, but he’s not that “strong” and doesn’t put up big numbers. I even saw a photo of him doing leg extensions, so I assume he’s not doing anything terribly heavy.

Based on the thoughts of Jeremy Lawson, I assume that Bolt is very “strong” in some way but it doesn’t necessarily show in the weight room. He can demonstrate strength on the track, but not on traditional lifts like the squat, deadlift or clean.

So, if the fastest man in the world and one of the greatest tight ends in the NFL aren’t overly strong on those lifts, should we really be putting a huge emphasis on them?

To take it one step further, think about the strongest person you know. I know a guy in my area who squatted over 1000 lbs. Can he run fast? Jump high? Move quickly or athletically? NO! Not at all. He’s good at lifting weights, which is awesome, but it hasn’t helped him in other areas. The transfer seems pretty limited.

You see, spending all of your time working on big numbers takes away a lot of time and energy from improving athleticism. Even the Olympic lifts do this in my opinion. I’ve seen a TON of great athletes who don’t clean much at all. Most of them won’t even think about snatching. I’ve also seen a lot of athletes who can pull a ton of weight, but they can’t get it done on the field.

Related: How to Use the Maximal Effort Method to Build Stronger Athletes

I guess this whole thought process has just created more questions than answers for me. I don’t know how much strength is “enough” and I’m not going to stop athletes from lifting. I guess I’m going to continue to look for ways that elicit good results in minimal time with an emphasis on safety. I don’t ever want to get an athlete hurt, and I’ve injured myself enough to recognize that it’s not worth it.

This discussion will definitely continue, and I’d love to hear your thoughts. Feel free to respond below and let me know what you’ve discovered in your own training.

Jim Kielbaso

Website: jimkielbaso.com

Twitter: @JimKielbaso